Coherence (physics)

In physics, coherence is a property of waves that enables stationary (i.e. temporally and spatially constant) interference. More generally, coherence describes all properties of the correlation between physical quantities of a wave.

When interfering, two waves can add together to create a larger wave (constructive interference) or subtract from each other to create a smaller wave (destructive interference), depending on their relative phase. Two waves are said to be coherent if they have a constant relative phase. The degree of coherence is measured by the interference visibility, a measure of how perfectly the waves can cancel due to destructive interference.

Contents |

Introduction

Coherence was originally introduced in connection with Young’s double-slit experiment in optics but is now used in any field that involves waves, such as acoustics, electrical engineering, neuroscience, and quantum physics. The property of coherence is the basis for commercial applications such as holography, the Sagnac gyroscope, radio antenna arrays, optical coherence tomography and telescope interferometers (astronomical optical interferometers and radio telescopes).

Coherence and correlation

The coherence of two waves follows from how well correlated the waves are as quantified by the cross-correlation function[1][2][3][4][5]. The cross-correlation quantifies the ability to predict the value of the second wave by knowing the value of the first. As an example, consider two waves perfectly correlated for all times. At any time, if the first wave changes, the second will change in the same way. If combined they can exhibit complete constructive interference/superposition at all times. It follows that they are perfectly coherent. As will be discussed below, the second wave need not be a separate entity. It could be the first wave at a different time or position. In this case, the measure of correlation is the autocorrelation function (sometimes called self-coherence).

Examples of wave-like states

These states are unified by the fact that their behavior is described by a wave equation or some generalization thereof.

- Waves in a rope (up and down) or slinky (compression and expansion)

- Surface waves in a liquid

- Electric signals (fields) in transmission cables

- Sound

- Radio waves and Microwaves

- Light waves (optics)

- Electrons, atoms and any other object (as described by quantum physics)

In most of these systems, one can measure the wave directly. Consequently, its correlation with another wave can simply be calculated. However, in optics one cannot measure the electric field directly as it oscillates much faster than any detector’s time resolution.[6] Instead, we measure the intensity of the light. Most of the concepts involving coherence which will be introduced below were developed in the field of optics and then used in other fields. Therefore, many of the standard measurements of coherence are indirect measurements, even in fields where the wave can be measured directly.

Temporal coherence

Temporal coherence is the measure of the average correlation between the value of a wave at any pair of times, separated by delay τ. Temporal coherence tells us how monochromatic a source is. In other words, it characterizes how well a wave can interfere with itself at a different time. The delay over which the phase or amplitude wanders by a significant amount (and hence the correlation decreases by significant amount) is defined as the coherence time τc. At τ=0 the degree of coherence is perfect whereas it drops significantly by delay τc. The coherence length Lc is defined as the distance the wave travels in time τc.

One should be careful not to confuse the coherence time with the time duration of the signal, nor the coherence length with the coherence area (see below).

The relationship between coherence time and bandwidth

It can be shown that the faster a wave decorrelates (and hence the smaller τc is) the larger the range of frequencies Δf the wave contains. Thus there is a tradeoff:

.

.

Formally, this follows from the convolution theorem in mathematics, which relates the Fourier transform of the power spectrum (the intensity of each frequency) to its autocorrelation.

Examples of temporal coherence

We consider four examples of temporal coherence.

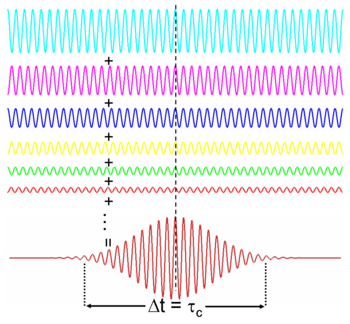

- A wave containing only a single frequency (monochromatic) is perfectly correlated at all times according to the above relation. (See Figure 1)

- Conversely, a wave whose phase drifts quickly will have a short coherence time. (See Figure 2)

- Similarly, pulses (wave packets) of waves, which naturally have a broad range of frequencies, also have a short coherence time since the amplitude of the wave changes quickly. (See Figure 3)

- Finally, white light, which has a very broad range of frequencies, is a wave which varies quickly in both amplitude and phase. Since it consequently has a very short coherence time (just 10 periods or so), it is often called incoherent.

The most monochromatic sources are usually lasers; such high monochromaticity implies long coherence lengths (up to hundreds of meters). For example, a stabilized helium-neon laser can produce light with coherence lengths in excess of 5 m. Not all lasers are monochromatic, however (e.g. for a mode-locked Ti-sapphire laser, Δλ ≈ 2 nm - 70 nm). LEDs are characterized by Δλ ≈ 50 nm, and tungsten filament lights exhibit Δλ ≈ 600 nm, so these sources have shorter coherence times than the most monochromatic lasers.

Holography requires light with a long coherence time. In contrast, Optical coherence tomography uses light with a short coherence time.

Measurement of temporal coherence

In optics, temporal coherence is measured in an interferometer such as the Michelson interferometer or Mach-Zehnder interferometer. In these devices, a wave is combined with a copy of itself that is delayed by time τ. A detector measures the time-averaged intensity of the light exiting the interferometer. The resulting interference visibility (e.g. see Figure 4) gives the temporal coherence at delay τ. Since for most natural light sources, the coherence time is much shorter than the time resolution of any detector, the detector itself does the time averaging. Consider the example shown in Figure 3. At a fixed delay, here 2τc, an infinitely fast detector would measure an intensity that fluctuates significantly over a time t equal to τc. In this case, to find the temporal coherence at 2τc, one would manually time-average the intensity.

Spatial coherence

In some systems, such as water waves or optics, wave-like states can extend over one or two dimensions. Spatial coherence describes the ability for two points in space, x1 and x2, in the extent of a wave to interfere, when averaged over time. More precisely, the spatial coherence is the cross-correlation between two points in a wave for all times. If a wave has only 1 value of amplitude over an infinite length, it is perfectly spatially coherent. The range of separation between the two points over which there is significant interference is called the coherence area, Ac. This is the relevant type of coherence for the Young’s double-slit interferometer. It is also used in optical imaging systems and particularly in various types of astronomy telescopes. Sometimes people also use “spatial coherence” to refer to the visibility when a wave-like state is combined with a spatially shifted copy of itself.

Examples of spatial coherence

Figure 5: A plane wave with an infinite coherence length. |

Figure 6: A wave with a varying profile (wavefront) and infinite coherence length. |

Figure 7: A wave with a varying profile (wavefront) and finite coherence length. |

Figure 8: A wave with finite coherence area is incident on a pinhole (small aperture). The wave will diffract out of the pinhole. Far from the pinhole the emerging spherical wavefronts are approximately flat. The coherence area is now infinite while the coherence length is unchanged. |

Figure 9: A wave with infinite coherence area is combined with a spatially-shifted copy of itself. Some sections in the wave interfere constructively and some will interfere destructively. Averaging over these sections, a detector with length D will measure reduced interference visibility. For example a misaligned Mach-Zehnder interferometer will do this. |

Consider a tungsten light-bulb filament. Different points in the filament emit light independently and have no fixed phase-relationship. In detail, at any point in time the profile of the emitted light is going to be distorted. The profile will change randomly over the coherence time  . Since for a white-light source such as a light-bulb

. Since for a white-light source such as a light-bulb  is small, the filament is considered a spatially incoherent source. In contrast, a radio antenna array, has large spatial coherence because antennas at opposite ends of the array emit with a fixed phase-relationship. Light waves produced by a laser often have high temporal and spatial coherence (though the degree of coherence depends strongly on the exact properties of the laser). Spatial coherence of laser beams also manifests itself as speckle patterns and diffraction fringes seen at the edges of shadow.

is small, the filament is considered a spatially incoherent source. In contrast, a radio antenna array, has large spatial coherence because antennas at opposite ends of the array emit with a fixed phase-relationship. Light waves produced by a laser often have high temporal and spatial coherence (though the degree of coherence depends strongly on the exact properties of the laser). Spatial coherence of laser beams also manifests itself as speckle patterns and diffraction fringes seen at the edges of shadow.

Holography requires temporally and spatially coherent light. Its inventor, Dennis Gabor, produced successful holograms more than ten years before lasers were invented. To produce coherent light he passed the monochromatic light from an emission line of a mercury-vapor lamp through a pinhole spatial filter.

Spectral coherence

Waves of different frequencies (in light these are different colours) can interfere to form a pulse if they have a fixed relative phase-relationship (see Fourier transform). Conversely, if waves of different frequencies are not coherent, then, when combined, they create a wave that is continuous in time (e.g. white light or white noise). The temporal duration of the pulse  is limited by the spectral bandwidth of the light

is limited by the spectral bandwidth of the light  according to:

according to:

,

,

which follows from the properties of the Fourier transform (for quantum particles it also results in the Heisenberg uncertainty principle).

If the phase depends linearly on the frequency (i.e.  ) then the pulse will have the minimum time duration for its bandwidth (a transform-limited pulse), otherwise it is chirped (see dispersion).

) then the pulse will have the minimum time duration for its bandwidth (a transform-limited pulse), otherwise it is chirped (see dispersion).

Measurement of spectral coherence

Measurement of the spectral coherence of light requires a nonlinear optical interferometer, such as an intensity optical correlator, frequency-resolved optical gating (FROG), or Spectral phase interferometry for direct electric-field reconstruction (SPIDER).

Polarization coherence

Light also has a polarization, which is the direction in which the electric field oscillates. Unpolarized light is composed of two equally intense incoherent light waves with orthogonal polarizations. The electric field of the unpolarized light wanders in every direction and changes in phase over the coherence time of the two light waves. A polarizer rotated to any angle will always transmit half the incident intensity when averaged over time.

If the electric field wanders by a smaller amount the light will be partially polarized so that at some angle, the polarizer will transmit more than half the intensity. If a wave is combined with an orthogonally polarized copy of itself delayed by less than the coherence time, partially polarized light is created.

The polarization of a light beam is represented by a vector in the Poincare sphere. For polarized light the end of the vector lies on the surface of the sphere, whereas the vector has zero length for unpolarized light. The vector for partially polarized light lies within the sphere

Applications

Holography

Coherent superpositions of optical wave fields include holography. Holographic objects are used frequently in daily life in bank notes and credit cards.

Non-optical wave fields

Further applications concern the coherent superposition of non-optical wave fields. In quantum mechanics for example one considers a probability field, which is related to the wave function  (interpretation: density of the probability amplitude). Here the applications concern, among others, the future technologies of quantum computing and the already available technology of quantum cryptography. Additionally the problems of the following subchapter are treated.

(interpretation: density of the probability amplitude). Here the applications concern, among others, the future technologies of quantum computing and the already available technology of quantum cryptography. Additionally the problems of the following subchapter are treated.

Quantum coherence and the range limitation problem

In quantum mechanics, all objects have wave-like properties (see de Broglie waves). For instance, in Young's double-slit experiment electrons can be used in the place of light waves. Each electron can go through either slit and hence has two paths that it can take to a particular final position. In quantum mechanics these two paths interfere. If there is destructive interference, the electron never arrives at that particular position. This ability to interfere is called quantum coherence.

The quantum description of perfectly coherent paths is called a pure state, in which the two paths are combined in a superposition. The correlation between the two particles exceeds what would be predicted for classical correlation alone (see Bell's inequalities). If this two-particle system is decohered (which would occur in a measurement via Einselection), then there is no longer any phase relationship between the two states. The quantum description of imperfectly coherent paths is called a mixed state, described by a density matrix (also called the "statistical operator") and is entirely analogous to a classical system of mixed probabilities (the correlations are classical).

Large-scale (macroscopic) quantum coherence leads to novel phenomena. For instance, the laser, superconductivity, and superfluidity are examples of highly coherent quantum systems. One example that shows the amazing possibilities of macroscopic quantum coherence is the Schrödinger's cat thought experiment. Another example of quantum coherence is in a Bose–Einstein condensate. Here, all the atoms that make up the condensate are in-phase; they are thus necessarily all described by a single quantum wavefunction.

See also

- Atomic coherence

- Coherence length

- Coherence width

- Coherent state

- Optical heterodyne detection

- Quantum decoherence

- Quantum Zeno effect

- Measurement problem

- Measurement in quantum mechanics

References

- ↑ Rolf G. Winter; Aephraim M. Steinberg. Coherence. AccessScience@McGraw-Hill. doi:10.1036/1097-8542.146900. http://www.accessscience.com.

- ↑ M.Born; E. Wolf (1999). Principles of Optics (7th ed. ed.).

- ↑ Loudon, Rodney (2000). The Quantum Theory of Light. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-850177-3.

- ↑ Leonard Mandel (1995). Optical Coherence and Quantum Optics. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0521417112.

- ↑ Arvind Marathay (1982). Elements of Optical Coherence Theory. John Wiley & Sons Inc. ISBN 0471567892.

- ↑ http://www.springerlink.com/content/l80m18140241381l/